Croatia’s ‘Feral Tribune’: The State Strikes Back

Povezani članci

The second part of BIRN’s series on ‘Feral Tribune’ looks at how the Croatian authorities hit back against the iconic anti-establishment magazine, crippling the satirical publication’s finances with lawsuits and taxes.

After its launch in June 1993, satirical weekly Feral Tribune, based in the Croatian coastal city of Split, quickly became the most prominent anti-establishment voice on the government-controlled media scene.

When its best-known front page, showing the Croatian and Serbian Presidents Franjo Tudjman and Slobodan Milosevic half-naked in bed with each other, received acclaim around the world, the authorities quickly responded by mobilising its editor-in-chief Viktor Ivancic into the Croatian Army.

Although Ivancic was soon back after a curtailed period of military training, Feral would feel the wrath of the state for years to come.

Full-scale assault on Feral

|

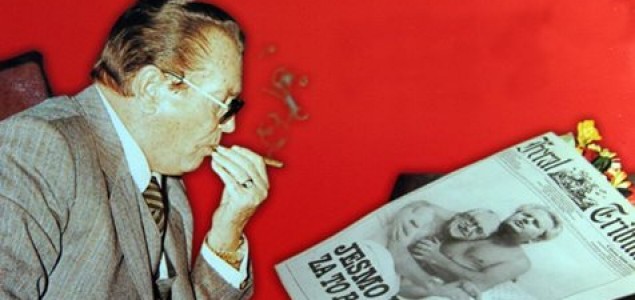

| Viktor Ivancic begins his working week with a trip to court under police escort. Photo courtesy of Leo Nikolic. |

The famous front page marked the beginning of more serious attempts by the authorities to cripple Feral.

As well as criticism from government officials and ruling Croatian Democratic Union, HDZ figures, accusing the magazine of expressing anti-Croatian sentiments at a time of war, there was everyday intimidation of neighbours and friends of Feral’s staff.

Then there were the lawsuits instigated by the state.

“There were lawsuits against us for ten, 20, 50,000 [German] marks coming in every day; those were millions of marks in claims. If someone sued Feral, of course, Croatian courts ruled in his favour,” said Boris Dezulovic, one of the founders and editors of the magazine.

In 1994, according to a decision made by Culture Minister Vesna Girardi-Jurkic, a special income tax was also slapped on Feral which was usually reserved for pornographic magazines.

“We paid this tax, almost 50,000 [German] marks a month, for ten months,” Ivancic explained, although the Constitutional Court then ruled that imposing the tax on the magazine was unconstitutional.

The logic behind the imposition of the tax was the use of semi-naked bodies on the covers, like those of Tudjman, Milosevic and others.

Feral also lost part of its revenue because Slobodna Dalmacija newspaper, which owned newspaper stands in Split, did not pay the magazine for the issues it had sold. The magazine’s editors saw the hand of the state at work in this too.

“There is one transcript of a conversation between Ivic Pasalic [Tudjman’s adviser for internal affairs] and Franjo Tudjman, in which Tudjman asks Pasalic how ‘is the thing with Feral going’, and he cold-bloodedly replies that they managed to reduce the circulation by tens of thousands of copies,” said Dezulovic.

According to Dezulovic, newspaper distributors would also send too many copies of Feral to smaller towns, many of which would be left unsold, and too few copies would be sent to cities – where the bulk of the magazine’s readers lived. The result was a fall in circulation and a consequent impact on finances.

Investigative journalism in a hostile environment

|

| Photo from Feral‘s report showing people stealing goods from a shopping mall in Knin after the military operation ‘Storm’ in August 1995. Photo: Hrvoje Polan. |

Until the end of the 1990s, Feral represented almost the only influential opposition to the HDZ administration on the media scene.

In 2000, after the death of Tudjman, when it became possible to look at files held by the Constitutional Order Protection Service, SZUP, many of Feral‘s journalists and editors found evidence that they had been wiretapped by the authorites.

Feral staff also believe that the secret services were probably behind incidents in June 1995, when three men took issues of the magazine from newsstands in central Split and publicly burned them.

“It’s fascinating because they did it for hours in the city centre; it went on and on… and nobody could say anything to them. The police, who stood by the side of them, did nothing. Usually, you can’t even take out a grill and put a fish on it in the city centre,” Ivancic said.

Feral had good investigative journalists who published stories that included reports on corruption scandals and war crimes committed by Croatian forces during the 1990s.

One was the revelation that crimes were committed by members of a reservist police battalion – under the command of Tomislav Mercep, who was convicted of war crimes in 2017 – against Serb civilians in Pakracka Poljana in 1991.

|

| “Stop The War In Croatia” – Feral‘s cover referring to a popular 1991 peace song, published during Croatia’s military operation ‘Storm’ in August 1995; “We’ll Build an Even Nicer and Older Bridge” – a sarcastic cover referring to Mostar’s Old Bridge, destroyed by Bosnian Croat forces in November 1993. |

In September 1997, Miro Bajramovic, a former member of the reservist police battalion, gave details of these murders in an interview with a 20-year-old Feral journalist, Ivica Djikic. After publishing the story, Feral had to be given police protection because of the death threats its staff received.

Feral had been faced with similarly fierce reactions two years earlier when in August 1995 it reported about large-scale robberies of Serb-owned houses and shops in the town of Knin and the surrounding Krajina area after the Croatian military’s victorious operation ‘Storm’.

“Everything we saw in Konavle [in southern Croatia] in 1991 when Montenegrin reservists robbed rich [army] captains’ homes, when they were taking away refrigerators, televisions and video recorders… we saw four years later in Krajina,” Dezulovic said.

The Krajina region had been under the control of Croatian Serb rebels, but once they were defeated in Operation Storm, an orgy of looting began, he explained.

|

| The montage of a half-naked Tudjman and Milosevic remained one of Feral‘s favourite motifs. Photo courtesy of Leo Nikolic. |

“We saw convoys, not of soldiers and reservists, but civilians; our neighbours who went there from Split by cars, vans, buses, trains; each one as they could. They went to Krajina, entered a house and took everything they could, even doors, light switches and power sockets. It was unprecedented pillage and a stain on Croatia’s conscience,” he said.

The story brought criticism even from some who were sympathetic to Feral, arguing that Operation Storm liberated Croatian territory from Serb occupation.

Editor-in-chief Ivancic said that Feral’s revelations were “mostly things that others didn’t want to talk about, and there wasn’t much need to investigate something”.

“One just had to lift the rug and published what was swept under it,” he added, laughing.

“We were practically alone among the free media for a time, and all that we published was exclusive. It came about that that five years later, other media published the same stories that we already published,” he recalled.

Face-to-face with a war criminal

|

| Pilic recalling his visit to Vukovar in 1997. Photo: Sven Milekic/BIRN. |

In 1997, one Feral’s better reporters, Damir Pilic, went to Vukovar, which had been besieged and destroyed by the Yugoslav People’s Army and Serb paramilitaries during the war.

At that point it was going through a United Nations-led process of peaceful reintegration with Croatia.

When he walked into Vukovar, Pilic heard a song by the Serbian singer Djordje Balasevic playing from a café and went inside. The waiter told him to come back later.

“I arrived in the evening… and as soon as I went in, I saw that the waiter was slightly uneasy, as if he was telling me: ‘Get out, get out.’ However, I didn’t register that immediately,” Pilic recalled.

%20receiving%20the%201998%20Olof%20Palme%20Memorial%20Award%20for%20International%20Understanding%20and%20Common%20Security%20in%20Stockholm%20in%201999.%20Photo%20EPA%20PRESSENS%20BILD%20GUNNAR%20SEIJBOLD%20pg%20940.jpg) |

| Ivancic (left) receiving the 1998 Olof Palme Memorial Award for International Understanding and Common Security in Stockholm in 1999. Photo: EPA/PRESSENS BILD GUNNAR SEIJBOLD. |

After he said hello to the waiter, he saw a group of five or six men who “didn’t look friendly at all”.

“Especially one of them who was playing pinball; he was huge, with big hair and a beard,” he said.

At one moment, a UN officer walked in to buy cigarettes, and the bearded man kicked him in the back and threw him out of the bar.

One of the men overheard Pilic’s Split dialect and asked if he was a Croat; Pilic replied that he was.

“And then, like a scene from the movies when the music stops; everything stops; silence. Then, the guy by the pinball machine comes up, looks at me and says: ‘Do you know who I am?’ I reply that I don’t know who he is,” he continued.

,%20Dezulovic%20(middle)%20and%20Lucic%20-%20more%20than%20brothers.%20Photo%20courtesy%20of%20Leo%20Nikolic%20940.jpg) |

| The magazine’s founders Ivancic (left), Dezulovic (central) and Lucic. Photo courtesy of Leo Nikolic. |

“He said: ‘Well, I was at Ovcara and you’re here now. So why did you come here?’” Pilic recalled.

Ovcara was where Serbian paramilitaries killed about 260 captured Croat soldiers and civilians after the fall of Vukovar in November 1991.

Pilic said that he only managed to save himself by reacting quickly.

“I told him: ‘I came here, because, for all of my life I have listened to how hospitality and guests are sacred for Serbs, and I wanted to see if that was only a fairy story or there is some truth to it.’ He stood there, looking at me for a few seconds and said: ‘Well, you’ve heard it well, no one will touch you.’”

Then, Pilic said, the big man ordered the waiter: “Give the man what he drinks.”

Tudjman dies, Feral hits hard times

|

| Lucic, Feral‘s own ‘Google’. Photo courtesy of Leo Nikolic. |

Although many thought Feral would lose its reason for existing when its nemesis Franjo Tudjman died in December 1999 and his HDZ party subsequently lost power in January 2000, it continued to publish until June 2008.

In the post-Tudjman era, Feral continued to reveal the shortcomings of the centre-left government that succeeded the HDZ, as well as the nationalist narratives that persisted in Croatian society.

| Predrag Lucic: Feral’s Own ‘Google’

Predrag Lucic, part of Feral’s founding trio, played a huge role in the creation of the magazine, writing satirical contributions, editing columns and working on the final edit of each issue. Lucic passed away in January this year, leaving behind a rich legacy in poetry, satire and journalism – although despite the fact that he received many awards for his volumes of poetry, not a single one was ever stocked by public libraries in Croatia. “Predrag, Viktor [Ivancic] and I were always more than brothers. It is not just a professional relationship; we are extremely connected,” Boris Dezulovic said. In a column for the weekly newspaper Novosti in which he said goodbye to Lucic, Dezulovic wrote that his colleague served as an information service for Feral with his intellect and knowledge – and that his death left him without a source of reliable information. “He was our Google. It’s really unbelievable what kind of a memory and how organised a brain Predrag had,” Dezulovic said, referring to his colleague’s knowledge of literature, art, history and politics, as well as his recollection of everything that was ever published in Feral. “Predrag’s role was enormous. We all worked together. Predrag and I sometimes sat for two hours just thinking about captions under a photo. I can’t even articulate it because the way we worked wasn’t typical for newspaper editorial departments,” Ivancic said. |

But working for Feral became harder over the years for its staff, because of the taxes that were imposed on the magazine and the lack of revenue due to the total absence of advertisers – something that was unique in Croatia’s media sphere.

“To publish a newspaper for 15 years without a single ad, I think it’s probably a world record,” Dezulovic said with an ironic smirk.

In the early 2000s, when the mainstream media was liberalised, some of Feral’s journalists left for other outlets.

“Despite all this, the quality of the magazine itself did not fall through the years. In fact, after all, we did a lot of work because half the amount of people working did the same job equally well. That end could actually have come earlier in 2005 and not in 2008. It was actually the agony of a patient dying of cancer,” explained Leo Nikolic, Feral’s graphic designer.

“Feral lasted longer than it objectively should have done. Simply due to our sheer masochism, we held out for 15 years, if you look at the circumstances under which we worked; you don’t know if you will be able to pay people salaries. We stopped when we couldn’t do it anymore,” Ivancic said.

Although Feral received donations from the Open Society Foundation and other foreign benefactors, this funding started to decrease in the late 1990s and virtually ended in 2000.

|

| Feral‘s last issue on June 20, 2008; Feral’s article “Regarding & In Spite Of: The Other Side of Satire” from 1996, analysing Tudjman’s reconciliation idea that was modelled on Spanish dictator Francisco Franco’s concept. Photo courtesy of Leo Nikolic. |

Feral also received loans from the US-based Media Development Loan Fund, MDLF, which became part of the magazine’s ownership structure in the early 2000s. But because the editorial staff rejected MDLF’s suggestions that they produce a more commercially-marketable product, their collaboration soon ended.

In its final years, Feral explored several options to try to save itself from financial ruin, negotiating with the daily newspaper Novi List from Rijeka and the largest Croatian news publisher, Europa Press Holding, EPH. The talks failed however, and the end was nigh.

Feral published its last issue on June 20, 2008, with Charlie Chaplin on the cover and the headline “Hit the Road”.

Despite all that they went through, most of the people who worked at Feralremain proud of what they achieved.

“It was absolutely worth it, that was the best time of my life,” Pilic said.

|

| Nikolic modelling (right) for another Feral cover satirising Tudjman (left). Photo courtesy of Leo Nikolic. |

Nikolic admitted that “in the end, we were defeated” – but he added that the satirical magazine lasted longer than predicted.

“Although everyone thought we would last for a maximum of five or six years, we were there for 15 years,” he said.

“In spite of everything, I’m not even sorry that in 1993, I took the first opportunity to show this to everyone,” he concluded, holding up his middle finger.

ENG

ENG